Double Dream

It's all Paul Blakeman's fault. Dear, gentle, soft spoken Paul, a good friend for several years, now gone where the powder is always dry.

Paul loved muzzleloading shotguns. He shot them, bought and sold them, repaired them, studied the history of them, and, over a period of ten years, taught me a lot about them. We spent many a pleasant hour just sitting and talking about them. I miss him.

One day when I showed up at his house he took me into his bedroom and pulled a bundle wrapped in an old quilt from under the bed. Handing it to me, he bade me open it. Inside was the most beautiful shotgun I have ever seen. It was an original double flint fowler, eighteenth century French, in about 24 gauge, long and slender. The metal was browned, the wood a delicate blond European walnut, the balance exquisite. The entire gun was a work of art, with ornately engraved inlaid metal and beautifully carved wood. I was struck by how light and thin and graceful the piece was, and was overcome with lust.

I let him know at once that I wanted to buy the gun, but he hadn't decided that he wanted to sell it then. He eventually did, but alas, not to me.

From that moment I knew I would own a double flintlock shotgun someday, but a shooter, not a museum piece. For six years I looked for a substitute, with no success. Then, in the November/December 1989 Muzzleloader, Bill Scurlock did a very positive review of a double flint shotgun made by J. T. Phillips of Beede, Arkansas. When I saw the pictures I knew I had found my gun, and called in an order for a 20 gauge at once.

The gun arrived in July, 1990, and is everything I had hoped. Beautiful dark American walnut stock with an early, heavy butt, a high comb and a lot of drop at the heel. Slender, tapered 32 inch barrels, iron furniture lightly engraved, and an attractive, old looking dark brown finish to the metal. The Cochran locks are neat, small, and very fast. It is a working gun, beautiful for the graceful lines and utilitarian simplicity. And she points, like a dream.

The gun arrived in July, 1990, and is everything I had hoped. Beautiful dark American walnut stock with an early, heavy butt, a high comb and a lot of drop at the heel. Slender, tapered 32 inch barrels, iron furniture lightly engraved, and an attractive, old looking dark brown finish to the metal. The Cochran locks are neat, small, and very fast. It is a working gun, beautiful for the graceful lines and utilitarian simplicity. And she points, like a dream.

Now, I had never fired a flintlock shotgun, but had been shooting a flintlock rifle and percussion shotguns for years, so I didn't feel like a total beginner. I knew how to make her shoot, but found out quickly I didn't know how to make her hit!

If you haven't tried moving targets with a flintlock shotgun, I don't want to hear what a fantastic shot you are. Save it for the ladies. My admiration for our pioneer forebears went up several notches, quickly.

I hate patterning shotguns, but I put in a couple of casual sessions with the flinter. Shooting 60 gr. FFFg, .125 overpowder card, 1/2 inch paper felt cushion wad, equal volume of #5 shot at 25 yards, the gun did well. Considering that both barrels are cylinder bore, that is.

Squirrel season is the first to open in Kentucky, and I anxiously awaited the opportunity to try the new gun. I always hunt squirrels with my flintlock rifle, but decided to use the shotgun a few times to see if it would work. It did. I took my first game with a flintlock shotgun, and it was very pleasing.

I don't need to shoot a limit or fill my game bag to get a real thrill out of hunting. I switched from modern weapons almost completely about 20 years ago, and have never regretted it for one moment. There is something extra for me in black powder hunting that I never found in hunting with modern weapons. It isn't just the greater challenge, but something deeper, something that satisfies a need to meet the game on more even ground. To earn the right to kill game by putting more of myself into the task is important to me, whether I'm hunting rabbits or deer. Somehow, black powder fills that need, and the evolution from modern to percussion to flint has been a very satisfying trek. Black powder has made me a better hunter, and made me feel like a better man.

When dove season opened I was out there banging away . . . and banging, and banging. I must have shot a dozen times before that first dove fell, but I have never killed one that gave me more of a thrill. I get a lot of shooting, and come home looking as if I've been mining coal, but I'll never be a threat to the dove population. That is the point, though, isn't it?

I taught myself to shoot as a kid, and like many who do that, I developed into an instinctive, or snap shooter. I don't consciously swing through or sustain a lead, I shoot where they are going to be. Put me to pass shooting ducks and I'm dead. Look out on a covey flush, though.

You can't do that with a flintlock. The lock time is fast on my gun, but never exactly the same from shot to shot. If you don't use sustained lead you won't hit consistently. Period. So, I had to learn to use a new type of gun and teach myself to lead simultaneously. Not easy, and I am not good at it yet.

Rabbit season brought a new set of challenges. I knocked so many rabbits down in the back end and then finished them with the second barrel, that I started referring to the back barrel and front barrel. But the rabbits tasted as great as always, and, ever so slowly, I was learning to shoot a double flint.

From the beginning the versatility of the smoothbore intrigued me, and I thought I would enjoy shooting roundball in it, maybe for deer. Kentucky whitetails are usually shot from short range and in the brush, and the shotgun would offer that second shot, if needed. I ordered a .600 inch Rapine roundball mold and cast up a bunch to try it.

Shooting from a rest at 25 yards I fired 12 shots from each barrel. I used 70, 80, 90, and 100 gr. FFg, .125 inch overpowder card, 1/2 inch paper felt cushion wad saturated with melted Crisco, and the roundball tightly patched with pillow ticking. You could have knocked me over with the proverbial feather! With 80 gr. I shot a 3 shot group 1 inch on centers with the right barrel, and only slightly bigger with the left. And that with only the bead sight.

Shooting a duplicate string from each barrel from 50 yards gave larger groups, roughly 4 to 5 inches. Standing up like a man and shooting offhand, I could keep all shots in the 6 inch bull at 25 yards. I felt I had myself a deer gun.

By now, the gun and I were on good terms. She is light to carry, fast swinging and a natural pointer. Rarely do I get a misfire if I do my part, and the lock time is very short. With her graceful lines and sexy color she looks mighty good on my arm, and she is a time machine. Whenever I hunt with her, I tread the ground of 1770.

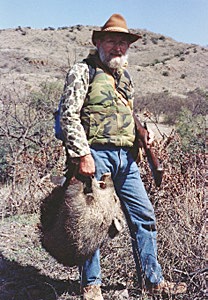

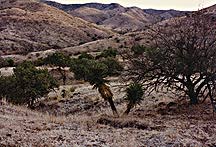

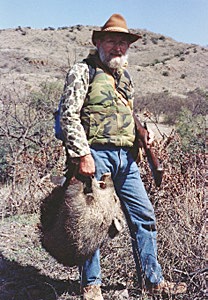

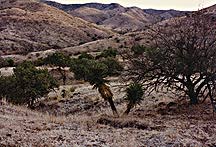

My dear friend "Skip", of Las Vegas, said "Go west, old man, and we will hunt javelina in the desert." So I did. In February of 1992 we wound up camped at the foot of a beautiful desert mountain in Arizona, with rugged, arid and thorny terrain all around us.

This old Kentucky boy took some time getting used to the exotic landscape. Everywhere was the cholla, manzanita, mesquite, live oak, ocotillo, cat claw, yucca, and prickly pear that pass for vegetation out there, and not a hickory tree in sight. I learned quickly that everything you touch is sharp.

This old Kentucky boy took some time getting used to the exotic landscape. Everywhere was the cholla, manzanita, mesquite, live oak, ocotillo, cat claw, yucca, and prickly pear that pass for vegetation out there, and not a hickory tree in sight. I learned quickly that everything you touch is sharp.

When I arrived Skip had already killed his pig, a young boar. He had used his .40 cal. Southgate flintlock rifle, and it was his first game with a flintlock. He is a very experienced and excellent hunter of all types of western big game, including grizzly. He got a special thrill from that shot, though, because he sneaked up to within 15 yards and took it with one clean shot with a flintlock.

Of course, I had brought the flint 20 gauge. Anticipating the possibility of a 50 yard shot, I selected a load of 90 gr. FFg.

The routine was to climb the mountain just after good light, sit all day glassing the valley below for pigs, peel off the top if game was sighted, and stalk up for the shot. We didn't see anything the first day.

The routine was to climb the mountain just after good light, sit all day glassing the valley below for pigs, peel off the top if game was sighted, and stalk up for the shot. We didn't see anything the first day.

Monday, Skip decided to take a day in camp, so I climbed the hill alone. All the huffing and puffing was because I wasn't acclimated to the altitude yet, not because I'm old. At 0915 I spotted a sounder of 7 pigs, a good 3/4 mile away, and drifting farther. I located what landmarks I could to keep myself oriented, checked the wind, and scrambled down the steep south slope of the mountain. After an hour of fighting through the cat claw and becoming disoriented several times, I found one javelina about 150 yards away in deep trash. I was well and truly downwind of him, so I sat and glassed until I had located 4 others, and figured the rest were in the same area. I had the thought that I could easily take him from there if I were shooting a scoped rifle.

A deep draw lay between us, so I had to make a long detour to cross to their side. Keeping low and watching the wind, I made the other side and started toward them, across the wind. When within 50 yards I shed my pack, canteen and wiping stick and started ever so slowly through the jumble of broken rocks and heavy vegetation. My heart was pounding in my ears as I inched forward, trying to look everywhere at once, to hear everything. Suddenly, about 25 yards ahead, there was a pig, standing broadside and feeding on a century plant.

Never taking my eyes off the pig, I dropped to hands and knees and crawled slowly forward till I had covered about 7 more yards, then slightly right to clear a shooting lane. Cocking the right lock, still on my knees, I aimed at the vital area and touched the trigger.

Never taking my eyes off the pig, I dropped to hands and knees and crawled slowly forward till I had covered about 7 more yards, then slightly right to clear a shooting lane. Cocking the right lock, still on my knees, I aimed at the vital area and touched the trigger.

Ninety grains of FFg makes a lot of smoke. Before the view was blotted out, I saw the pig drop absolutely straight down. He never moved. All around me in the dense cover I heard and saw the rest of the pigs scatter. I cocked the left barrel and walked slowly forward, saw that he was dead, and eased the hammer.

Have you ever stood all alone in a vast, rugged landscape far from home and heard yourself laughing aloud? I have. It feels grand.

My dream, which had its beginning in Paul Blakeman's bedroom so many years before, had come to fruition there in that beautiful spot. I was a pig hunter. I had stalked and killed my game in fair chase with a flintlock shotgun, one shot, clean and quick.

I sat by the javelina and spent a few moments of quiet thought, adjusting to the feelings of gladness and sorrow that always flood over me after a successful hunt, communing with the spirit of the pig. Being thankful, asking forgiveness.

The ordeal of carrying that pig over the mountain and down to camp is another story. I have never done anything so strenuous. When I arrived in camp and had rehydrated myself, Skip supervised my skinning the pig and hanging the meat so I could say "I can't believe I did the whole thing!"

Sitting on the ridge that evening, sipping a glass of wine and philosophizing while watching the marvelous sunset, something Skip and I always do when we can manage it, I was at peace with the world.

Sitting on the ridge that evening, sipping a glass of wine and philosophizing while watching the marvelous sunset, something Skip and I always do when we can manage it, I was at peace with the world.

The shotgun and I are very good friends now. If I'm good enough I'll take a deer with it one day, and maybe even a turkey. My fascination with the gun and with black powder shooting continues to grow, and I fade back in time more as the years slide by. My understanding of and appreciation for the lifestyle of our ancestors increases every time I take her to the field. What better way could there be to study American history?

An afternoon spent in the field with that gun on my arm is worth more than all the psychiatrists have to offer. Thank you, Paul.

©1995 B.E. Spencer

Photos #1, #5 & #6 by Otto L. Buss

Back to  The gun arrived in July, 1990, and is everything I had hoped. Beautiful dark American walnut stock with an early, heavy butt, a high comb and a lot of drop at the heel. Slender, tapered 32 inch barrels, iron furniture lightly engraved, and an attractive, old looking dark brown finish to the metal. The Cochran locks are neat, small, and very fast. It is a working gun, beautiful for the graceful lines and utilitarian simplicity. And she points, like a dream.

The gun arrived in July, 1990, and is everything I had hoped. Beautiful dark American walnut stock with an early, heavy butt, a high comb and a lot of drop at the heel. Slender, tapered 32 inch barrels, iron furniture lightly engraved, and an attractive, old looking dark brown finish to the metal. The Cochran locks are neat, small, and very fast. It is a working gun, beautiful for the graceful lines and utilitarian simplicity. And she points, like a dream.

This old Kentucky boy took some time getting used to the exotic landscape. Everywhere was the cholla, manzanita, mesquite, live oak, ocotillo, cat claw, yucca, and prickly pear that pass for vegetation out there, and not a hickory tree in sight. I learned quickly that everything you touch is sharp.

This old Kentucky boy took some time getting used to the exotic landscape. Everywhere was the cholla, manzanita, mesquite, live oak, ocotillo, cat claw, yucca, and prickly pear that pass for vegetation out there, and not a hickory tree in sight. I learned quickly that everything you touch is sharp. The routine was to climb the mountain just after good light, sit all day glassing the valley below for pigs, peel off the top if game was sighted, and stalk up for the shot. We didn't see anything the first day.

The routine was to climb the mountain just after good light, sit all day glassing the valley below for pigs, peel off the top if game was sighted, and stalk up for the shot. We didn't see anything the first day. Never taking my eyes off the pig, I dropped to hands and knees and crawled slowly forward till I had covered about 7 more yards, then slightly right to clear a shooting lane. Cocking the right lock, still on my knees, I aimed at the vital area and touched the trigger.

Never taking my eyes off the pig, I dropped to hands and knees and crawled slowly forward till I had covered about 7 more yards, then slightly right to clear a shooting lane. Cocking the right lock, still on my knees, I aimed at the vital area and touched the trigger. Sitting on the ridge that evening, sipping a glass of wine and philosophizing while watching the marvelous sunset, something Skip and I always do when we can manage it, I was at peace with the world.

Sitting on the ridge that evening, sipping a glass of wine and philosophizing while watching the marvelous sunset, something Skip and I always do when we can manage it, I was at peace with the world.