Ongoing Fusion Research at

MIT

Submitted

by: Leo Wehner

Late last summer I had the opportunity to visit the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. My son, Daniel, had been accepted into a doctoral program in the Health Sciences department and our family decided to visit him to see how the small-town, young man was managing in the Cambridge and Boston metropolis.

As we entered his dormitory, I couldn’t help but notice the small white sign on the door of an old red brick building across the street. In simply stated, “Fusion Lab”. Further down the street was another door with a sign, “Plasma Science and Fusion Center”. As a senior in high school, I had become fascinated with the subject of fusion and its potential for supplying the future energy needs of the world. The year was 1975, and the best estimates at that time predicted that commercial production of electricity from fusion was 30 years away. This would be a great opportunity to investigate how close we have come towards meeting those estimates. Although my son was involved in the medical department on the other side of campus and avoided any contact with “Physics”, he had a friend who knew a friend who could arrange a tour of the facility. Since I controlled the credit card on this trip, the rest of the family thought the tour would be a great idea too.

Before I describe what we saw on the tour, it would be a good idea to briefly discuss what “fusion” is. The nucleus of an atom consists of protons and neutrons. Since the protons have a positive electrical charge, and like charges repel each other, there must be a powerful force that keeps the nucleus from flying apart. This force is called the “strong force”. The amount of energy that you would have to expend to overcome the strong force and split the nucleus is called the “binding energy”. All elements have a binding energy that is unique to their specific structure. Deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen, contains one proton and one neutron and has a specific binding energy. Helium contains two protons and two neutrons and possesses less binding energy than the binding energy of two deuterium atoms. Therefore, if you could get two deuterium atoms to fuse into one helium atom, the surplus binding energy would be released. The released energy could then be used in the production of electricity. Sounds simple, doesn’t it?

Two deuterium atoms combine into one helium atom and

release the surplus binding energy.

As discussed earlier, protons contain the same positive electrical charge and will repel each other. Consequently, a tremendous amount of energy is required to bring the nuclei close enough for the strong force to bind them into a single new nucleus. The energy required is a combination of high temperature and pressure. This has been the challenge for fusion research for the past 50 years. The high temperatures (approximately 100 million degrees centigrade) required for fusion to occur affect the atoms in the matter that you are trying to fuse. At these high temperatures, matter doesn’t exist as a solid, liquid, or gas, but rather in a fourth state called “plasma”. A plasma is a gaseous sea of positively charged atoms called ions and free negatively charged electrons. The behavior of plasma is extremely complex and controlling it has been one of the main engineering challenges that must be overcome.

Once the

plasma is created, it has to be handled or confined. There are three basic ways to confine a plasma. The first is the method the sun uses: gravity.

If you have a big enough ball of plasma, it will stick together by

gravity, and be self-confining. Unfortunately for fusion researchers, that

doesn't work here on earth. The second

method is that used in nuclear fusion bombs: you implode a small pellet of fusion fuel. If you do it quickly enough, and compress it

hard enough, the temperature will increase rapidly, and so will the density. Because the inertia of the imploding pellet

keeps it momentarily confined, this method is known as inertial

confinement. Inertial confinement is

also being studied using linear accelerators and lasers. The third method uses the fact that charged

particles placed in a magnetic field will gyrate in circles. If you can arrange the magnetic field

carefully, the particles will be trapped by it. If you can trap them well enough, the plasma energy will be

confined. Then you can heat the plasma,

and achieve fusion. This method is

known as magnetic confinement. Initial

heating is achieved by a

combination

of microwaves, energetic/accelerated particle beams, and resistive (ohmic)

heating from currents driven through the plasma. Magnetic confinement is the method used by the MIT research team.

The magnetic

and heating fields of a plasma confined to a toroidal shape.

At the

beginning of the Fusion Lab tour at MIT, I soon became aware of the enormous

project being undertaken within the walls of the old, red brick building. This was not the typical laboratory with

counter tops filled with beakers, Bunsen burners, and glass tubing. Rather, it was more like a construction site

complete with hard hats and safety glasses.

It turns out that every three years, the fusion “machine” is dismantled

for inspection, modification, and maintenance.

Our tour guide informed us that we had walked in on the maintenance

outage of the heart of the largest single research project at MIT: the Alcator C-mod experiment. The Alcator C-mod machine belongs to a class

of devices called tokamaks, which use magnets to confine the plasma in a donut

shape called a torus. The word Alcator

is an acronym derived from the Italian words Alto Campo Torus, meaning high

field torus. The Alcator’s high field

strength lets researchers experiment with plasmas hotter and denser than machines

of similar size in other parts of the world.

The toroidal field has a strength of 9 Tesla while the ohmic heating

field produces a field strength of 22 Tesla.

For comparison, a typical Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) machine used

in the medical field produces a field strength of about 1.5 Tesla.

A view of

the Alcator Fusion Machine during initial assembly (top cover removed).

The Alcator machine consists of a vacuum vessel that is 10 feet in diameter and approximately 20 feet high. The top and bottom covers are 26 inches thick with each cover weighing 35 tons. Even this massive structure will yield to the extreme forces produced during operation. During each period of pulsed operation, the toroidal magnets exert a force of 25,000,000 lbs on each of the tokamak’s cover plates causing them to deflect approximately 1/8 inch. Because of the enormous forces involved during operation, the entire structure is held together with 96 “draw bars” or bolts that connect the covers to the center cylinder. Each draw bar is pretensioned to 500,000 lbs during installation.

One of 96 Draw Bars

Pretensioning the Drawbars

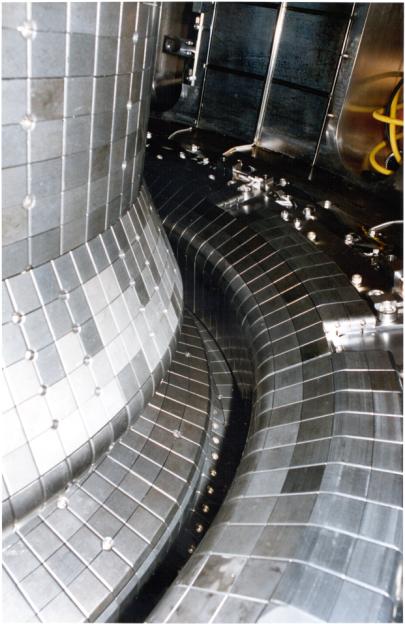

At the start of a fusion experiment, frozen hydrogen fuel pellets are injected (shot) into the torus. Additional gaseous hydrogen fuel is also “puffed” into the plasma. Large currents of electricity are passed through the fuel, which causes rapid heating. For fusion to occur, plasma must be kept well away from the walls of the vacuum vessel. The confinement is never perfect, however, and some plasma eventually leaks through the confining fields. If the high-energy plasma comes in contact with the walls, two things happen. First, damage to the vessel wall is a concern. For this reason, the walls of the vessel are lined with Molybdenum tiles similar to the heat shields that protect the underside of the space shuttles. Second, plasma that escapes confinement rapidly cools which then contaminates the “hot” plasma. The Alcator C-mod has a unique divertor system which uses specially shaped magnetic fields to “scrape” away the cooler, outer edge of the plasma, draw it into an isolated channel on the bottom of the vessel, and then pump it out of the machine. Efficient divertor systems will be key elements in future fusion plants.

Viewing the Molybdenum tile lining of the torus with

divertor channel at bottom.

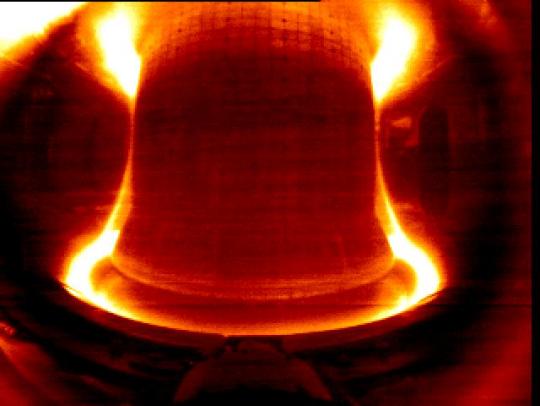

Ions in the center of the plasma circulate around the magnetic field lines 80 million times each second. The plasma is heated by the pulsed ohmic heating field which produces a heating current of 3 million amps. To boost the temperature of the plasma even higher, two radio antennae inject radio waves at 80 MHz into the circulating particles. This causes the central ions to absorb another 4 million watts of power. The result is a plasma that is pulsed up to approximately 100 million degrees centigrade. Fusion of the deuterium atoms into helium atoms occurs for approximately 4 seconds during the pulse.

View of radio frequency antennae.

Video shot of confined plasma. The plasma is so hot that only its outer edge emits visible

radiation.

This whole process makes a person wonder how much power is required just to initiate a 4 second pulse of fusion. First, the ohmic heating current is approximately 3 million amps. Add to that an additional 4 million watts of power provided by the radio frequency antennae. The toroidal field windings consume an additional 265 thousand amps of electrical current. Therefore, the power consumed by a 4 second pulse of fusion can approach one gigawatt of electricity. There is no way that the local utility in Cambridge can supply this magnitude of power even for short periods of time, so MIT has resorted to producing their own short term power needs. Located behind the building is a giant motor-generator set. A 2000 horsepower electrical motor spins an alternator and flywheel at 1800 rpm. Together, the 75 ton flywheel and 120 ton alternator rotor store approximately two billion joules of energy. At precisely the right time, this energy source is tapped into the main electrical system. A maximum performance pulse consumes over a quarter of this energy in about 3 seconds. During some experiments, the Alcator C-mod machine has approached the “break even” point meaning it produces an output equal to the energy that it consumes. With this magnitude of energy being consumed and produced, even for short durations, a great deal of heat is generated. The entire structure is cooled by liquid nitrogen and a cooling period of at least 15 minutes is required between pulses.

During our tour, it became obvious that the team members involved in the project were energetic and dedicated individuals. The project has involved almost every department at MIT due to the complexity of the mathematics, engineering, physics, and materials science. The focus of the team is to learn better control techniques for plasma confinement and refinement of divertor design and operation. This ever increasing knowledge will be applied to the next generation of fusion machines. Today, there are several fusion research projects throughout the world that are slowly solving the engineering challenges that fusion presents. While optimistic about the role that fusion will play in meeting the energy needs of the world in the future, I believe that it will take several years to go from the research phase today to the production phase of tomorrow. When questioned about the prognosis for commercial production of electricity from this promising technology, the director of the project stated with a smile on his face, “About 30 years”.

(various text and photos used with permission by the Plasma Science and Fusion Center of MIT)

Leo Wehner has worked at the Byron Station nuclear plant since 1982. He received a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and is a licensed Professional Engineer in the state of Illinois. Since starting at Byron he has held a variety of positions in the Engineering, Regulatory Assurance, and Operating departments. Leo is currently a Senior Reactor Operator working as a Unit Supervisor in the main control room.