Bob said, "Alright, she's all yours. Take her around a few times." I couldn't believe my ears, and I craned my neck, trying to see his face, to find if he was serious. He was, because he flipped his shoulder harness back and began climbing from the front cockpit. He was telling me that he thought I was ready for my solo flight in the Stearman. Since I had only about eight hours in the plane with him as instructor, it came as a complete surprise and it was difficult to believe the moment had come.

Sitting there on the taxi strip next to the tower at Bowman Field in Louisville, Kentucky, I wasn't at all certain he knew what he was doing. Like every man who has experienced that moment, I was suddenly struck with the certainty that he was wrong, that I wasn't ready.

Sure, I wasn't the usual student pilot, since I had flown in the Navy years before, but I had expected to have to put in the full twenty hours, or so, that ordinarily precedes this moment. I was aware that all the old skills were coming back rapidly, and I was beginning to feel comfortable in the plane, but solo? Now? You gotta be kidding!

Nothing for it but to do it, so I waved and began to taxi toward the runway. Slowly and carefully I "S"-turned the plane to the hold-clear line and went through the take-off check list. Tower cleared me to the active runway and for touch-and -go landings, so I taxied out and lined her up. Hooo-boy! Here we go!

This wasn't my first time in this situation. It had happened before, in 1954, at an outlying field at the Whiting Field Naval Air Station near Pensacola, Florida. That time I was flying a Navy North American SNJ (Air Force AT-6). It, too, was a tailwheel plane powered by a radial engine, but that was a different world, and I was just a kid of twenty years. Now I was a middle-aged man of forty-six, and my head worked differently. Very little of the fearless boy remained.

One last check of the wind shows it to be very light to calm. At least I won't have to deal with a crosswind, the bane of all tailwheel pilots, especially those flying old wood and cloth biplanes. The old birds will turn on you in a second in a crosswind, trying to swap ends in a vicious maneuver called a ground loop. Many a wingtip has been shredded in that way, and worse.

Full-rich mixture, tail wheel locked, cycle the flight controls one last time, kick both rudder pedals to remind myself to stay on them, and advance the throttle quickly but smoothly to full power. The plane begins to move, and I hold the stick full back while stretching my neck to the left to watch the runway. God, she is big! All that fuselage, both those wings, all those wires seem to block out everything I need to see. The roar of the engine is impressive, but smooth. When it feels right, I ease the stick forward to raise the tail...too suddenly, nose veering to the left, right rudder to straighten out... and the wind begins to whip at my face as acceleration continues. The wings come alive, I can feel it in the stick, she's beginning to feel light, trying to tell me she wants to fly, but not yet, Old Girl, not yet. Hold her on a bit until the airspeed indicator shows 70 knots, then just let her float off while keeping the wings level and the nose straight down the runway. I'm flying solo, again. After twenty-five years, and in the plane of my dreams, a Stearman biplane. No, make that my Stearman biplane. I didn't giggle, but it was only because, as Steve Coonts says, you can't giggle and fly at the same time.

Straight out for a bit, then a smooth climbing turn to the left, reaching for pattern altitude. Line up parallel to the runway, throttle back and hold her level. My heart is pounding a bit, but I think I'm taking this very well, so far.

Level at 500 feet AGL, an apparent wing's length from the runway on the downwind leg, just like in the Navy. Quickly, far too quickly, the time to begin the landing arrives. Tension is a palpable thing in the air, my palms are sweaty, my pulse and breathing are speeding up, and I'm already talking to myself. Getting this old bird off the ground is child's play compared to getting it back on again. When the bottom left wing is even with the point of intended impact (Don't say that!), ease the power back a bit, wait until the speed begins to decrease and begin a smooth turn down and to the left.

A perfect landing in the Naval training command required you to gauge things very nicely. You must make a 180 degree turn while losing all your altitude, and wind up lined straight down the runway at ground level. If you did it just right, the last of the power came off, the wings came level, the nose pointed straight down the runway and the plane stalled just above the runway, all at exactly the same moment. That's the theory, anyway.

I was acutely aware of the problems which could arise while trying to make this actually happen. I was there on a day when it all went spectacularly wrong for one student pilot. As student pilots, we were assigned "runway duty" for a couple of hours while we were trying to learn this landing technique. The idea was to let us see how it looked from the ground, to better understand what we should do. An RDO (Runway Duty Officer) and an assistant were stationed at the end of the runway. The RDO was in radio contact with the student doing the landing, and the assistant had red flags to wave as a signal to abort the landing, a "wave-off". A student made an approach normal in every way except that he wasn't turning enough. He was maintaining proper airspeed and losing altitude correctly, but his turning profile was such that his wings would come level with the nose of the plane still pointing far to the right of the runway center line, not lined up down it. The RDO began telling him to turn more, turn more, but he did not respond. The RDO got louder and more insistent as the plane approached the touch-down point, but, still, no response, no correction. The RDO ordered him to go around, and the assistant began waving those big red flags. No response. The plane was getting very close now, and the RDO understood that there was a severe problem.

Sitting up there in the SNJ, the student was locked in, concentrating totally on what he was trying to do, and had turned his brain off to everything else. The RDO was yelling in his ears, but he wasn't hearing it. Finally, he saw that he hadn't turned enough, so he began turning more, more, more. The plane was really racked over, now, in a steep bank, and the student was really pulling on that nose.

By this time, the plane was only a few feet high, and the left wing was pointed almost straight at the ground. In desperation, the RDO fired a red flare at the plane, trying to get the pilot's attention. His aim was too good. He hit the windscreen right in front of the student's face. That snapped him back to the reality of his situation, and, in a panic, he slammed the throttle forward with great force. You can't do that. Those old radial engines will quit if you try it. His did.

Wing tip fifteen feet from the ground, airspeed about 70 knots, bank angle about 75 degrees, and the engine stopped. Well, even I knew what was coming, and it did. The plane instantly stalled and slid to the ground. The left wing tip hit first and that wing sheared off. The nose hit next, and that parted company right in front of the cockpit. Right wing and tail section of the fuselage followed in rapid succession as the plane cartwheeled through the grass at an angle to the runway. Noise, dust, smoke! That cockpit section of the plane ended its tumbling journey about 200 yards down the runway, sitting flat on its bottom. No wheels, they had gone with the wings. Strewn along its path were the various chunks of the plane it had shed on its way. Thank, God, no fire... yet.

A long moment of silence as we all stared, and then all hell broke lose. Emergency crash crews, fire truck, sirens... reminded me of that old Navy saying, "When in danger, fear or doubt, run in circles, scream and shout!"

We all ran to the plane, and were amazed to see the pilot still sitting there, hands on the throttle and stick, feet on the rudders, radio cord still plugged in. His plane had left him, a little at a time, but he was still flying.

The canopy had slammed shut, and it took a moment for that to be opened, but then the student calmly released and threw back his shoulder belts, unplugged his radio and climbed out. On the side of an SNJ there is a half-moon step for you to use while entering or leaving the cockpit. He put his foot on the step and swung his weight out, which shifted the center of gravity of his little piece of his plane, and it rolled over on top of him, pinning him to the ground. He was not injured in the slightest except for a small cut on his forehead. That happened when the cockpit section rolled on and smashed his flight helmet.

Much to the surprise of the other students, he was allowed to continue his training. Bad habits are hard to break, however. Many months later, this same student flew to the aircraft carrier USS Saipan out in the Gulf of Mexico, made six acceptable landings on the carrier, returned to Barren Field and did almost the same accident again on landing there. This time he broke his arm. His naval flying career was terminated, this time.

Starting my turn for that first solo landing in the Stearman, I wasn't thinking about that incident, but it was squirreled away in my mind and added to the tension.

Milk the power, set up a steady rate of descent and turn, and just let it happen. If you set it up right at the start, you wind up right where you want to be. I did, but this plane was much lighter than the SNJ, and it didn't seem ready to return to the ground. A hot day, thermals off the end of the runway, and you really have to make this plane go down. Crank her around, milk the power, watch that speed, line her up, line her up...looking good. Level and almost on the ground, now, ease back the stick, a little more, a little more, hold it, hold it , ah, she's stalled and touches down slightly tail wheel first, then the mains. Suddenly, you aren't flying, anymore, but are in control of a really squirrely ground vehicle traveling at 60 knots and anxious for the opportunity to swap ends. Rudder, rudder, stick in your gut, keep her straight, right down the centerline. Once all is completely under control and the plane has slowed just a bit, add the power, again. The tail comes up quickly this time, since you are already moving fast, and before you can say it, you are flying once again. Straight out for a bit, then a smooth climbing turn to the left, reaching for pattern altitude.

My first solo take-off and landing in a tail-dragger in more than twenty-five years, the very first in a biplane, was behind me, and I wasn't dead, yet. No dings on the plane, either, which was almost as important.

I did three more of the same, then the last landing to a full stop, and taxied back to the pad. I must say, I felt different on the way back down that taxiway than I did on the way out.

I did three more of the same, then the last landing to a full stop, and taxied back to the pad. I must say, I felt different on the way back down that taxiway than I did on the way out.

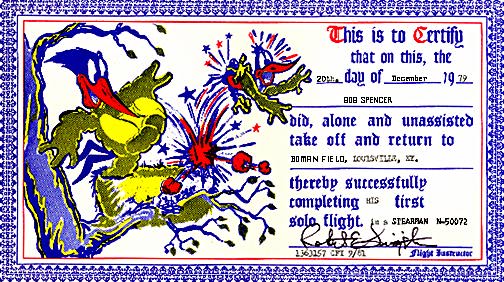

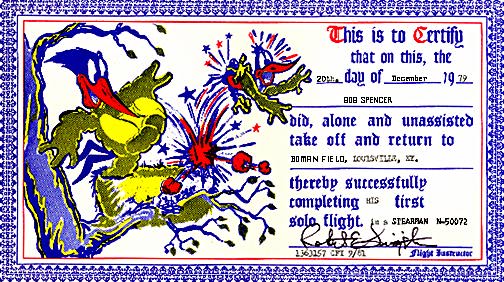

When I soloed in the Navy, my classmates cut off my tie and threw me in the swimming pool in full uniform. This time was much quieter, although there was considerable chattering, laughing and back slapping when Bob and I met on the line. We retired to the FBO for a cup of coffee, and Bob presented me with an "official certificate of solo", which I still look at from time to time with the greatest pleasure.

Stearman airplanes are special creations. No one who has never piloted one can really understand how they get in your blood, under your skin, and change your life. Maudlin, sentimental romanticism, to be sure. It all comes from within your own mind, but so what, the result is the same. This day was the beginning of an adventure which lasted eight years, and of a string of wonderful memories which will last for my lifetime.

Copyright © B. E. Spencer 2001 All rights reserved.