When I saw a dozen or so old yellow Stearman biplanes parked on the apron at Mainside NAS, Pensacola, Florida, during my tour there as a Naval Aviation Cadet (NAVCAD) in 1954-56, I never dreamed I would one day own one. Yet today I can say I have done so for eight years. Then, they were a curiosity, left over from the "old days", having been discontinued as training planes about five years before. Now, they are antiques, relatively rare, and are even more of a curiosity.

I seem to have always been aware of the Stearman. There is an eye-catching quality to them that refuses to be denied. For years I thought of them as crop dusters, and sometimes, as stunt planes, but not often as either. They were always there, though, filed away in the back of my mind. Now, as an owner and pilot of a Stearman, I have very different feelings about them, especially my own, N50072. These feelings are of many types, and they change from time to time, but they are no longer on the periphery of my mind.

Probably the most constant of all is the most difficult to express. Not many people can understand at all when I say the plane feels like a part of me, an extension of my own personality, but there is no other way to express it. The plane feels like a friend. I have owned and used many machines over the years, but with none of them has there been anything similar. With none of them have I ever found myself carrying on a conversation, yet that has happened numerous times with 50072. Obviously, this feeling is generated in my own head, but that in no way detracts from the seeming reality of the phenomenon. When I reflect, it is easily seen that the plane mirrors my own mood, usually. When I am feeling "up", the plane seems to go about the business of flying with vim and vigor, and everything about her works like the proverbial sewing machine. When I'm "down", the reverse is true, and the plane seems to resist, to drag her feet, to fly under protest. The human psyche being what it is, this is what one would expect, but there are also those curious times when it just doesn't work out that way.

If I am nervous, uncertain, or afraid while flying, there is a certain something which comes through to me which I find very reassuring. A feeling of "You can do it!". No. " We can do it!" A feeling of dependability and strength, of cooperation and help. I am always aware of the inherent strength of design and construction of the Stearman, of its gentle yet rugged way of doing things, and, certainly, the feelings I have at these times are nothing more than my internal computer accurately calculating probabilities. I am very glad, however, that the answer comes in the form of a friendly voice tugging at my awareness. There have been a few moments, from time to time, when I have been very glad.

History. As I grow older, I become more interested in the history of things, and in that vein, Zero-Seven-Two has been a treasure trove. At the ripe old age of 46 years, she has outlived the vast majority of her kind. The years have been full ones, indeed, beginning as a training plane at NAS Pensacola on October 3, 1940. There she flew 2300+ hours teaching Navy pilots. Can you just imagine the fantastic stories that old bird could tell? I've been through the training syllabus at Pensacola, and it blows my mind to think of the literally thousands of incidents which must have whirled around her. There must be hundreds of men who would have a funny or sad or scary memory of their flights in the plane. She was the third of her type to be accepted by the Navy, and very well may be the oldest living N2S-1. Just think of it!

After serving well in the military for five years, the plane embarked on her second career, crop dusting. For the next twenty-nine years she flew all over the midwest, a working plane. Fortunately, probably purely by chance, the plane was never "cut" for a big hopper, never fitted with a 450 horsepower engine. My mind fills with images of the procession of pilots, the tons of chemicals, the thousands of hours, of long, hot, grueling days. How can we explain the fact that throughout all that time the plane stayed intact, never was demolished, never was parted out as so many thousands of her sister ships were? I can't, but the fact of it fills me with a rush of gladness.

For the last ten years the old girl has been busy with her third career, that of being a full time pleasure aircraft. Completely rebuilt, bright and gleaming once again, she has been treated more gently, cared for more lovingly, and called upon to fly considerably less than in either of the other two. She has flown a Governor on the campaign trail, flown over the Parade of Tall Ships celebrating our country's 200th birthday, taught more people to fly, spent hours rolling about the blue sky in acrobatic routines, given dozens of people young and old their first open cockpit biplane ride, traveled distances great and small to many an air show and fly-in, and in general been having a gay old time. To us, one of these careers may seem more desirable than another, but it has never and will never be true for the plane. Single minded in every way, she just keeps on flying.

Many pilots and owners of Stearman airplanes don't want a plane that has been a duster. Just the opposite is true for me. I am very proud that my plane has had such a varied and useful career. Thinking of all the flow of time and events in her past, being aware of it as I stand and look at her, or work on her, or fly her ---these have given me as much pleasure as the flying.

In many ways I am a throwback when it comes to flying. I learned to fly in the Navy, in planes with a grip-filling stick instead of a "steering wheel", a real throttle quadrant worked with the left hand, good solid rudder pedals and toe brakes. There were three wheels, all right, but the third one was at the tail---where it belongs. You taxied in "S" curves in order to see where you were going, and if you braked just a little too hard with both main gears at the same time, you landed on your nose---where you belonged. Taxying, the way we did it, was just as exciting, more difficult, and about as much fun as the flying. I landed on an aircraft carrier 12 for 12, flew air-to-air gunnery runs so hard my nose bled, beat my instructor just once in a dog fight, landed an SNJ in a field so short there were leaves in the landing gear, flew formation so close another plane's prop cut my radio antenna, and never, in 140 flying hours in the training command, failed a check ride of any type. Yet, today, I am just as proud of the fact that, once upon a fairy-tale time long ago, I could, and many times did, taxi my plane from runway to line without letting the tail wheel touch the ground. Pilots, especially old ones, are terminally weird.

In many ways I am a throwback when it comes to flying. I learned to fly in the Navy, in planes with a grip-filling stick instead of a "steering wheel", a real throttle quadrant worked with the left hand, good solid rudder pedals and toe brakes. There were three wheels, all right, but the third one was at the tail---where it belongs. You taxied in "S" curves in order to see where you were going, and if you braked just a little too hard with both main gears at the same time, you landed on your nose---where you belonged. Taxying, the way we did it, was just as exciting, more difficult, and about as much fun as the flying. I landed on an aircraft carrier 12 for 12, flew air-to-air gunnery runs so hard my nose bled, beat my instructor just once in a dog fight, landed an SNJ in a field so short there were leaves in the landing gear, flew formation so close another plane's prop cut my radio antenna, and never, in 140 flying hours in the training command, failed a check ride of any type. Yet, today, I am just as proud of the fact that, once upon a fairy-tale time long ago, I could, and many times did, taxi my plane from runway to line without letting the tail wheel touch the ground. Pilots, especially old ones, are terminally weird.

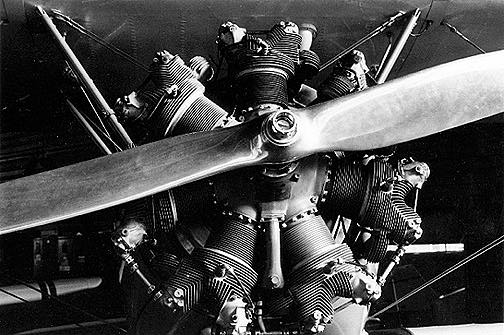

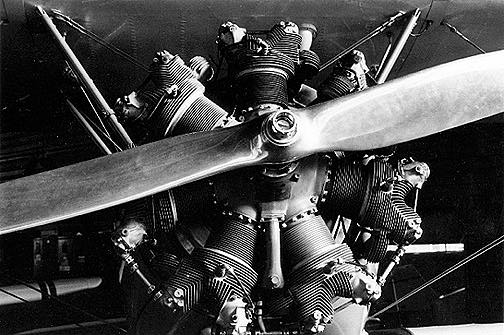

All of that intense brain-washing left me flawed when it comes to flying. If my plane doesn't fit those memories in my head, if I can't fly it with a helmet and goggles, a spring-loaded double shoulder harness, sitting on a parachute as hard as a stone, if I don't hear the slow throaty roar of a radial engine when I call for power, if I can't turn the beast upside down whenever I feel like it, then I really don't care if I fly or not. Actually, I would rather not fly.

So--- the Stearman being all of these things with an entire wing left over, I love everything about her. I feel privileged to have been allowed to fly in and with her. I feel strongly a sense of responsibility to her in that the plane is a page from history, a story not yet completely told, and it is my place to guard over her for the short time she is in my care. I am responsible to those who come after me who will fly and care for her. The knowledge that no other man may ever feel or discharge that same duty affects mine not at all. I know in my inner self that all those old pilots from days lost forever would approve, and that is more reward than I need. I have been for a short part of my life, by God, a pilot in the truest sense of the word. Nothing could possibly make me more proud.

Fear was always a part of my flying. At times, it was that sudden overwhelming rush of fear that made me want to scream, threatened to shut my mind off like a toggle switch, made me decide, ...no..., made me know without doubt that I would never walk away. Fear of an aviation fuel fire. Fear of becoming a mangled bloody lump in a twisted pile of wreckage. Fear of an inverted flat spin all the way in.

Fortunately these were rare and brief. Others were less intense, but tended to stay much longer. Fear of failure in front of my fellow pilots, of the ground loop on landing, of looking like a student in front of old pilots whom I admire so deeply, of doing some really stupid thing for which I will be remembered by all concerned for as long as the grass grows and the streams flow.

With the Stearman, it was mostly, and most acutely, the fear of damaging the plane. Maybe because the old-time mechanics are about as scarce as old time pilots and old cloth and wood planes, I always felt that if I damaged the plane in any way, she would never fly again, and the parting-out would begin. Happily that fear was never realized. Grow and flow.

If there was ever a pilot's motto, it must surely be that pride barely precedes a fall. A kind of pride, however, has been a mainstay in my relationship with N50072. I am, and will always be, more proud of being a Stearman pilot than of any other accomplishment. I am, and will always be, proud to say to any man that I was once a Stearman owner. I have been a man of eclectic interests. My mind moves from one fascination to the next, steadily and smoothly, soaking up new knowledge like a lamb at teat, really happy only when in the throes of some new venture. Knowing the little I do about the history and the flying and the being part of that plane has given me more joy than I can explain.

I have frequently been puzzled by my penchant for old-fashioned things. A real gun, to me, means black powder, hand made round balls, flintlock ignition, 100 yard maximum range. Traditional archery fits me like a glove, fills my need for a challenge, gives me the satisfying sensation of stepping back in time to a day more basic and natural. Other than certain flights in Zero-Seven-Two on very special occasions, sailboats in heavy wind in blue water have come as close to satisfying my inner being as anything. All these things seem better to me because the are simple, they require knowledge and skill, they depend very much on the human element for their real driving force. So do old wood and cloth, tail-dragging, open cockpit biplanes.

The sensations one experiences in flying low and slow in one of these old planes are so different than in any other plane that only we who have actually done it can really know what they are. The wind, the heat or cold, the sounds of the engine and the wing wires, the vibrations, the smell, the oily spray on your goggles---how can you describe them?

The view is different when framed between two wings. The frame is the essence of the whole experience. I consider myself fortunate indeed to have been one of the few who really understand in depth just what a marvelous thing a Stearman biplane is, and to appreciate how much more full my life has been made by having known one.

A Stearman is not a cheap plane to own and fly. But, as the pundit said, it's cheaper than psychoanalysis. And that is true. When you are washed by the deluge of pleasant sensations, of sights so beautiful they make a lump in your throat, of sounds that seem to vibrate your soul, and you are overcome by a feeling of total satisfaction and happiness, the troubles of the world absolutely disappear from your consciousness. It can surely only do a man good to be so completely caught up in the joy of the moment that he knows with certainty there is no other place he would rather be, nothing else he would rather be doing.

Sadness isn't an emotion I ever anticipated feeling in any intensity in conjunction with N50072. Oh, I've been sad that I didn't learn to fly her better, and that I didn't fly her more, didn't take advantage of more opportunities to log one of those memory-building flights. But now I am experiencing a sadness much more intense and painful, because N50072 has been sold. Within a week the plane will be, of all unpleasant places, in New Jersey. My short relationship with my Stearman is coming to an end. I'll miss her. I don't like the thought of no more trips to Galesburg, no more loops and hammer-heads, no more slipping the old crate steeply in to the runway and spearing the spot with verve. Not in the slightest.

Of all the feelings I associate with Zero-Seven-Two, the most important to me was that she made me feel young. Not many men would learn to fly again after twenty-four years of total abstinence, especially in an old, cranky, ground-looping beast. 1 did. And I felt young. Not many would get any joy out of long, long cross-country flights in cold weather in an open cockpit. I did. And I felt young. Who would learn again even the basic acrobatics at the age of forty-six? I did. And I felt young. Who would so gladly accept the responsibility of caring for the plane in that special way only a few men can even understand? I did. And I felt young. These things kept me involved, kept the juices flowing, filled my mind with wonderful images and memories, made me think more highly of myself. But now she's going. And I feel old. I no longer think of myself as a young man. Age has never bothered me, because I never thought about it. I just felt the same all the time--young. I could never remember my age without counting back. Now I can. I'm fifty-four. And I've had a coronary, and I don't fly Stearman biplanes anymore.

I don't really understand why I let myself make that decision to sell, I only know it was a mistake. I knew it the instant I met the first man who came to consider buying her. And he did.

It's strange how certain moments, otherwise nothing out of the ordinary, come to the front of your mind when you glance backward. I made many hundred landings in the Stearman, some great, most just fair, some really lousy. One sticks out, though. Bob and I were returning from some forgotten adventure, and I was flying. The pattern was a right-hand one, that day, and I eased the power and rolled onto base leg. Concentrating on hitting the spot, I noticed that several planes were lined up waiting for the runway after we landed, watching my approach. For reasons that maybe only those who have flown old rag-wing biplanes will understand, I held high until almost lined up, then kicked in hard right rudder and hard left stick, dropped the nose and set up a steep slip, with the plane sliding sideways through the air. I slipped a long way, not ever really looking at my airspeed indicator or altimeter, just flying by the seat of my pants, the sound of the air in the wing wires. When close to the ground just off the end of the runway, I neutralized the controls, leveled the wings and went into the flare, all at the same time. The plane stalled at least three feet in the air and hit the ground on all three wheels with a thump, right on the spot. The rollout was straight down the centerline, and it felt great. I immediately heard Bob on the intercom: "Once a carrier pilot, always a carrier pilot!" I never knew whether he was complimenting or criticizing me on the landing. I didn't matter, because I liked it, a lot. I didn't know it at that moment, but that was the last landing I ever made in Zero-Seven-Two. It's a good one to remember.

Time will pass, and I'm sure the pain and sadness will lessen. I have many wonderful memories to look back on, and they will serve me well. But I will never have a Stearman again. And even if by some weird quirk of fate I do, it will not be N50072, the oldest existing N2S-1.

Copyright © B. E. Spencer 2000 All rights reserved.